|

|

Paleoclimate

How do we know about the Ice Ages?

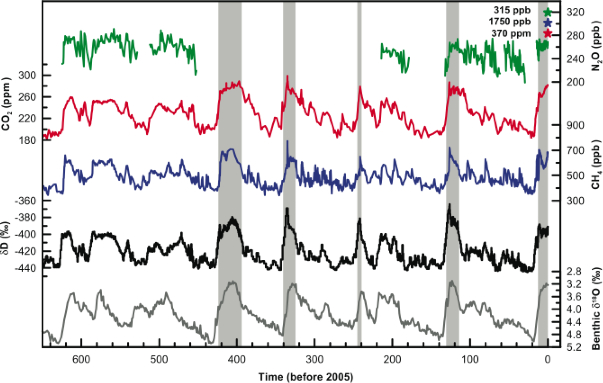

Scientists are able to learn about the Earth's atmosphere over the past several hundred thousand years from ice cores drilled out of ice sheets and glaciers. As ice freezes, air bubbles are trapped within the ice. The plot to the right from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) shows some important atmospheric gases as recorded in a European Project for Ice Coring in Antarctica (EPICA) ice core from Antarctica, which contains air bubbles from the past 650,000 years. The gray shading indicates interglacial periods like right now when there are relatively few ice sheets and glaciers.

The bottom two lines (black and gray) give us information about the temperatures

and amounts of ice. The black line is indicative of temperature. The numbers

to the left of these lines can be interpreted as the relative amount of hydrogen

atoms that are deuterium.

The bottom two lines (black and gray) give us information about the temperatures

and amounts of ice. The black line is indicative of temperature. The numbers

to the left of these lines can be interpreted as the relative amount of hydrogen

atoms that are deuterium.

Water molecules with deuterium are heavier than regular water molecules, and so they are less likely to evaporate than regular water molecules. During warm periods, like the interglacials, more water is evaporated from the oceans. This water has a low value on the left of the graph. Eventually, some of the evaporated water falls as precipitation and freezes into ice sheets and glaciers. These masses of ice are now "marked" because a higher than usual ratio of the hydrogen molecules are deuterium. During glacial periods, the ice cores have a high number and during interglacials the ice cores have a low one.

The gray line indicates ice volume changes. Like hydrogen, oxygen also has a

heavier version that weighs 18 grams (regular oxygen weighs 16 grams). The

values to the right of the grey line give the relative amount of 18O (the heavy

oxygen) in a sample. Oxygen can be stored in the skeletons of coral and other

marine life. This figure shows the relative 18O ratio for oxygen stored in

benthic foraminifera (fossilized remains of single-celled organisms that live on

or close to the ocean floor).

The gray line indicates ice volume changes. Like hydrogen, oxygen also has a

heavier version that weighs 18 grams (regular oxygen weighs 16 grams). The

values to the right of the grey line give the relative amount of 18O (the heavy

oxygen) in a sample. Oxygen can be stored in the skeletons of coral and other

marine life. This figure shows the relative 18O ratio for oxygen stored in

benthic foraminifera (fossilized remains of single-celled organisms that live on

or close to the ocean floor).

18O molecules tend to sink, so ice forming from ocean water tends to have more of the 16O. During glacial periods there is a relatively high amount of 18O in the oceans because much more of the 16O is being frozen. This oxygen gets incorporated into the foraminifera shells, which can be retrieved and studied by scientists millennia later. During glacial periods, the fossilized shells have a high relative 18O, and during interglacial periods there is a lower relative 18O.

Next page -> ice ages, continued

Links and resources

How do we know about the Ice Ages?

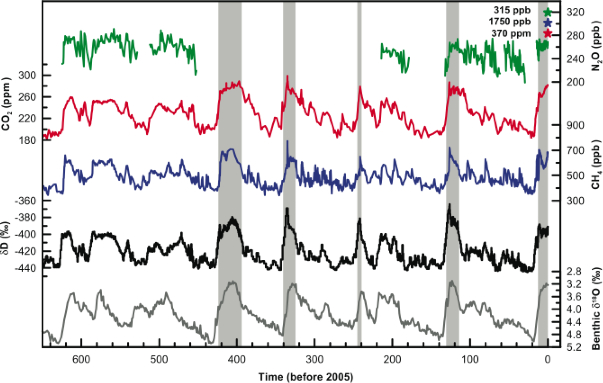

Scientists are able to learn about the Earth's atmosphere over the past several hundred thousand years from ice cores drilled out of ice sheets and glaciers. As ice freezes, air bubbles are trapped within the ice. The plot to the right from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) shows some important atmospheric gases as recorded in a European Project for Ice Coring in Antarctica (EPICA) ice core from Antarctica, which contains air bubbles from the past 650,000 years. The gray shading indicates interglacial periods like right now when there are relatively few ice sheets and glaciers.

The bottom two lines (black and gray) give us information about the temperatures

and amounts of ice. The black line is indicative of temperature. The numbers

to the left of these lines can be interpreted as the relative amount of hydrogen

atoms that are deuterium.

The bottom two lines (black and gray) give us information about the temperatures

and amounts of ice. The black line is indicative of temperature. The numbers

to the left of these lines can be interpreted as the relative amount of hydrogen

atoms that are deuterium.Water molecules with deuterium are heavier than regular water molecules, and so they are less likely to evaporate than regular water molecules. During warm periods, like the interglacials, more water is evaporated from the oceans. This water has a low value on the left of the graph. Eventually, some of the evaporated water falls as precipitation and freezes into ice sheets and glaciers. These masses of ice are now "marked" because a higher than usual ratio of the hydrogen molecules are deuterium. During glacial periods, the ice cores have a high number and during interglacials the ice cores have a low one.

The gray line indicates ice volume changes. Like hydrogen, oxygen also has a

heavier version that weighs 18 grams (regular oxygen weighs 16 grams). The

values to the right of the grey line give the relative amount of 18O (the heavy

oxygen) in a sample. Oxygen can be stored in the skeletons of coral and other

marine life. This figure shows the relative 18O ratio for oxygen stored in

benthic foraminifera (fossilized remains of single-celled organisms that live on

or close to the ocean floor).

The gray line indicates ice volume changes. Like hydrogen, oxygen also has a

heavier version that weighs 18 grams (regular oxygen weighs 16 grams). The

values to the right of the grey line give the relative amount of 18O (the heavy

oxygen) in a sample. Oxygen can be stored in the skeletons of coral and other

marine life. This figure shows the relative 18O ratio for oxygen stored in

benthic foraminifera (fossilized remains of single-celled organisms that live on

or close to the ocean floor).18O molecules tend to sink, so ice forming from ocean water tends to have more of the 16O. During glacial periods there is a relatively high amount of 18O in the oceans because much more of the 16O is being frozen. This oxygen gets incorporated into the foraminifera shells, which can be retrieved and studied by scientists millennia later. During glacial periods, the fossilized shells have a high relative 18O, and during interglacial periods there is a lower relative 18O.

Next page -> ice ages, continued

Links and resources