|

|

How Do Models Make Clouds?

for more advanced readers

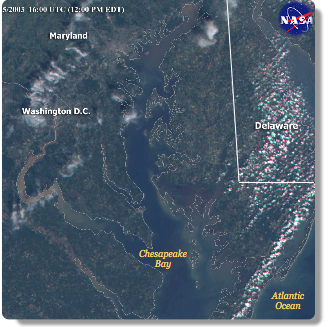

Clouds are smaller than the typical grid cell size. For example, a typical grid

cell might be about the size of Delaware - but imagine how many individual

clouds are above Delaware at any given time. The picture to the right was taken

from a

NASA satellite on September

25, 2003. You can see several clouds covering Delaware, at the top right of the

photo.

Even though they can be small, clouds are extremely important for the transport

of heat and moisture within the model. To complicate the scene,

condensation,

evaporation, and precipitation take place on an even smaller scale than

clouds. If each grid cell can only be described by one set of equations,

scientists have to find clever ways to represent small-scale processes. Instead

of calculating the small-scale processes individually, the models calculate

equations that represent, or

parameterize, the effects of

convection on the

larger-scale model variables.

For example, we know that if there is a lot of moist convection going on, there

will be certain effects on the surrounding atmosphere - such as changes in

albedo and temperature - and that there is likely to be precipitation of

some sort.

Regardless of their specific details, all representations of convection must

answer these key questions:

Clouds are smaller than the typical grid cell size. For example, a typical grid

cell might be about the size of Delaware - but imagine how many individual

clouds are above Delaware at any given time. The picture to the right was taken

from a

NASA satellite on September

25, 2003. You can see several clouds covering Delaware, at the top right of the

photo.

Even though they can be small, clouds are extremely important for the transport

of heat and moisture within the model. To complicate the scene,

condensation,

evaporation, and precipitation take place on an even smaller scale than

clouds. If each grid cell can only be described by one set of equations,

scientists have to find clever ways to represent small-scale processes. Instead

of calculating the small-scale processes individually, the models calculate

equations that represent, or

parameterize, the effects of

convection on the

larger-scale model variables.

For example, we know that if there is a lot of moist convection going on, there

will be certain effects on the surrounding atmosphere - such as changes in

albedo and temperature - and that there is likely to be precipitation of

some sort.

Regardless of their specific details, all representations of convection must

answer these key questions:

Next page -> how do models make clouds, continued

Links and resources

for more advanced readers

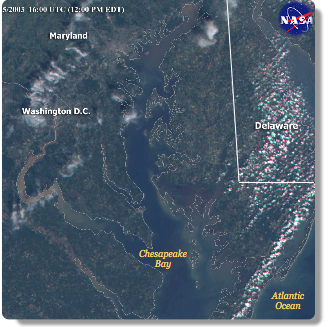

Clouds are smaller than the typical grid cell size. For example, a typical grid

cell might be about the size of Delaware - but imagine how many individual

clouds are above Delaware at any given time. The picture to the right was taken

from a

NASA satellite on September

25, 2003. You can see several clouds covering Delaware, at the top right of the

photo.

Even though they can be small, clouds are extremely important for the transport

of heat and moisture within the model. To complicate the scene,

condensation,

evaporation, and precipitation take place on an even smaller scale than

clouds. If each grid cell can only be described by one set of equations,

scientists have to find clever ways to represent small-scale processes. Instead

of calculating the small-scale processes individually, the models calculate

equations that represent, or

parameterize, the effects of

convection on the

larger-scale model variables.

For example, we know that if there is a lot of moist convection going on, there

will be certain effects on the surrounding atmosphere - such as changes in

albedo and temperature - and that there is likely to be precipitation of

some sort.

Regardless of their specific details, all representations of convection must

answer these key questions:

Clouds are smaller than the typical grid cell size. For example, a typical grid

cell might be about the size of Delaware - but imagine how many individual

clouds are above Delaware at any given time. The picture to the right was taken

from a

NASA satellite on September

25, 2003. You can see several clouds covering Delaware, at the top right of the

photo.

Even though they can be small, clouds are extremely important for the transport

of heat and moisture within the model. To complicate the scene,

condensation,

evaporation, and precipitation take place on an even smaller scale than

clouds. If each grid cell can only be described by one set of equations,

scientists have to find clever ways to represent small-scale processes. Instead

of calculating the small-scale processes individually, the models calculate

equations that represent, or

parameterize, the effects of

convection on the

larger-scale model variables.

For example, we know that if there is a lot of moist convection going on, there

will be certain effects on the surrounding atmosphere - such as changes in

albedo and temperature - and that there is likely to be precipitation of

some sort.

Regardless of their specific details, all representations of convection must

answer these key questions: - How does the large-scale weather pattern control the initiation, location, and intensity of convection?

- How does convection modify the atmosphere around it?

- What are the properties of the clouds that are too small to be simulated by the climate model?

Next page -> how do models make clouds, continued

Links and resources